Sipadan

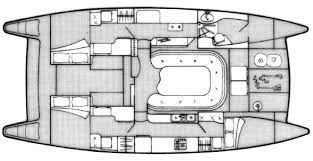

Layout

- 3 double cabins

- 2 heads with showers

- Saloon and open galley

Sails

- Main sail (plus one spare)

- Genoa

- Stay sail

- Spinnaker

Electronics

- Raymarine anemometer (new in 2020)

- Raymarine depth sounder (new in 2020)

Electrics

- Portable HONDA generator

- 5 new batteries (home and engine bank)

Dinghy

- Brand new, inflatable

- 2-stroke outboard

About the Prout 39 Escale

Construction

The construction (to Lloyd’s ISO 9002/BS5750 Quality Assurance, backed by a five-year anti-osmosis guarantee) is female-molded monocoque. Solid fiberglass is hand laid up with isophthalic resin below the waterline; the hull is Airex/Divincell— or balsa-cored above the waterline. A high-tech schedule of multi-axial cloths, a 1.5-to-1 resin-to-mat ratio and foam and balsa cores provides high tensile-strength, greater panel stiffness, and lower overall weight, the latter accomplishment being so important to multihull performance. This laminate adds insulation, sound-deadening and durability to the hull’s construction. Kevlar reinforcement and multi-axial cloth is used in high-stress areas for extra strength and weight-savings. Integral water tanks in the keels provide a double skin; buoyancy compartments fore and aft, combined with the sandwich construction and wood furniture, help make the Escale unsinkable. “The Prouts are very well built,” confirms Multihulls Chiodi. “The quality of manufacture is superb”.

Performance

Windward ability: Many monohull sailors think that catamarans do not go well to windward, but this opinion has often been formed after watching Hobie Cats struggle to weather, on which point of sail they are notoriously poor. The Prout Escale goes to windward almost as well as any cruising monohull, tacking through 90 to 95. Those same Escale 39-testers reported tacking angles of only 110, which is due to a lack of familiarity with multihulls in general and the Prout Escale 39 in particular. It takes a while to learn how to get the most out of multihulls, especially when beating and tacking, and over the years we’ve discovered many tricks that have enhanced the performance of our 39. Monohull sailors sailing multihulls tend to pinch up too much. Also, when tacking with a cruising catamaran, you must fall off a little, build up speed, then gradually sheet in and come up. We were able to sail from Los Roques in Venezuela to Martinique in the Leeward Islands via Peninsula de Paria (about 600 miles) against the trade winds and the contrary two-knot current without motoring.

Downwind: For passagemaking downwind, we would hand the main and pole out twin genoas, one hanked onto a temporary wire forestay. The gap between this and the furler foil acts as a vent allowing the sails to set better, while the poles give you an effective sailing beam of 36 feet. With the sail area so far forward, there is no tendency to broach.

The poles can be left set up for long passages, because the lack of rolling means that there is no danger of dipping the ends into the water. If it becomes necessary to turn upwind, say, to avoid a fishing boat. This can be done without interference from the poles. For broad-reaching, we used a poled-out asymmetrical spinnaker, and if there was a reasonable breeze, one of the two sail plans could be counted on to give us 160 to 180 miles a day, and the occasional 200-mile day. For most 35-foot LWL monohulls, these numbers would be unheard of, but for day-in/day-out Escale 39 passagemakers such as ourselves, they are fairly routine.

Heavy air: The Prout “minsail” rig employs a small (243 square feet) full-battened, no-roach mainsail, along with two roller-furling headsails. The mast, which is supported on the cruising rig by no less than 14 stays, is stepped aft, just forward of the cockpit, thus all halyards fall directly to hand in the cockpit. The genoa and staysail sheets and reefing lines are also led into the cockpit.

In heavy air, a double or triple-reefed main, combined with a partially-furled staysail, provides effective drive, a low center-of-effort, and great stability, given the beam of 18 feet 4 inches. In these catamarans, heaving-to is not always the best tactic, and I carried a couple of drogues for deployment off the stern to slow us down in big following seas, and an 18-foot-diameter parachute anchor for deployment off the bow when progress to windward was difficult. This held us stationary and safe, if not very comfortable, in a three-day Force 9/10 blow off North Africa, during which nine lives were lost from other vessels and from the coastline in the area.

Manoeuvrability

Under power: Twin diesels (18-horsepower Yanmar 2-GMs), one in each hull, allow the Escale to turn on the spot. In fact, the vessel can be handled quite well with one engine, as we found when we damaged a prop and went for many months with only one. Slim hulls and light displacement result in good fuel efficiency, a quarter of a gallon per hour per engine. Under sail: The Escale is very easy to handle in confined areas. Both the mainsail and the staysail are self-tacking, so all the helmsman needs to do is unfurl a small part of the genoa and sheet this in after tacking. The hydraulic steering system ensures that the rudder stays where you put it, while attending to the sails. We usually sailed the anchor out as well, which could be done single-handed as the windlass controls are located in the cockpit console on our vessel.

Cruising/living aboard

A number of different layouts are available. My vessel has two heads, one in each hull, and three double-berths, each 15 feet away from the others, which provides wonderful privacy. The athwartships double-berths aft are excellent sea berths on either tack. One hull is for the owner and the other for crew and friends. A large galley with triple-sink unit and a nav-station with full-size Admiralty chart table, helped to keep both crew and skipper happy. The saloon seats eight, with panoramic 360 degrees visibility and ready access into the cockpit. Fourteen hatches and four opening ports provide superb ventilation in the tropics. The deep cockpit, and built-in boarding ladders provide additional safety. Aft of the cockpit, there is a 12-foot-wide aft deck, which is ideal for dinghy stowage, either deflated and rolled up on passage, or simply left inflated while gunkholing. We used the same area for other equipment, too: stern anchor ready for instant deployment, snorkeling gear, supply of fresh coconuts, etc.

The deck design includes a water-catchment system that will fill the 170-gallons. tanks in 20 minutes of tropical rain. You simply open the side-deck fillers, place a rolled-up towel aft of them, and all the rain from the coachroof, foredeck and side decks flows into the tanks, thanks to the integral molded toe-rails. It is ironic that so many cruising boats nowadays are resorting to watermakers while allowing rain water to go to waste. The collection surfaces are so big on catamarans that a watermaker can usually take a supplemental role and therefore be smaller. We managed fine on rain water, plus an occasional visit to a shore-water supply.

The shallow draft (3 feet 3 inches) allows you to cruise areas where most vessels cannot venture, and can also reduce running costs. We did our own antifouling and sail-drive maintenance by drying out at low tide. On our boat, the keels themselves were protected by fiberglass keel shoes bonded onto the forward part of the keels.

Conclusion

The Prout 39 is built for blue water cruising and passagemaking, while being one of the prettiest catamarans you will ever see. She will look after her crew in just about any weather, but like any multihull, is vulnerable to overloading. Some comforts should be left at home. Although the price per foot is more than a monohull, the p catamaran design, introduced in 1991, is descended from a long pedigree of ocean cruising designs from Prout, such as the Quest 31 and 33, Event 34, Snowgoose 35 and 37, and the Ocean Ranger 45. Although this review is specific to the 39, many of the observations made are applicable to the other Prout designs. My comments are born of 22,000 nautical miles of offshore passagemaking, much of it singlehanded, on Escale 39s, 20,000 of these on my own 1993-built Escale, An t-Iompodh Deisiol which in Gaelic means “follow the sun.”

“Prout is the oldest manufacturer of stock multihulls, and they’ve produced an awful lot of boats,” said Charles Chiodi, publisher of Multihulls magazine. “They’ve got a very good track record, with a reputation for stable boats and a stable business.” Indeed, over 4,000 vessels have been built by Prout over a 40-year period, during which many lessons have been learned. How did some of these lessons manifest themselves in the Escale? Over some 10-million miles logged with Prout cruising catamarans, there reportedly have been no hull failures or capsizes of any Prout catamaran, including the Escale 39.

“Certainly, there have been a few accidents on Prouts,” Chiodi says, “but they haven’t been the fault of the boat, just poor seamanship on the part of the crew.” This success is a result of sticking to strict design parameters, which Prout themselves developed over a long period of time. When Lloyd’s of London was asked to provide construction ratings for catamarans, no data was available, so they simply adopted Prout’s database. This also was used in Japan in the 1980s, when the Japanese maritime regulations governing stability and safety were changed to accommodate multihulls.”

Boats.com, October 2004

The Boater’s Notes

Sipadan has benefited from a recent overhaul: 2 brand new Diesel engines, from the reputed BETA MARINE brand, now clocking 65 hours, new batteries, engine and house bank, fresh anti-foul. Built by the reputable British shipyard in the late 90s, the Prout 39 was designed a medium-sized passage maker, with proven blue water capability. Last anti fouled in December 2021. This is a rare opportunity: an attractively priced, well built catamaran, available in Hong Kong waters.